Map Academy: Designed for Disruption (NGLC)

By: Amanda Avallone, Learning Officer at Next Generation Learning Challenges in Boulder, CO

We designed Map Academy to be adaptable and resilient. We are the kind of school that we are because it is the only way to meet the needs of our students. We did not design our model for the pandemic—we were able to do a solid pivot, but the virus is not the reason why we are who we are.

— Rachel Babcock, co-director and co-founder, Map Academy

Across the NGLC national community of practice, school and district leaders are planning for the upcoming academic year. On a superficial level, this is a familiar summer activity, part of the traditional rhythm of the school calendar: taking stock, setting goals, hiring staff, ordering materials. Yet in so many ways, planning for next year feels as raw and strange as a venture into uncharted seas. As a result of the pandemic, educators and their communities are crafting multiple scenarios and contingency plans, grappling with many unknowns about when and how they will reopen schools and what learning will look like when they do. Educators, as well as learners, are coping as best they can with a major disruption to the world of school as we know it.

At the same time, many schools are embracing the idea of disruption and viewing it as an opportunity to transform learning. They are responding to the current crisis by rethinking their priorities, redefining student success, and redesigning school in essential ways—coming together to make learning more equitable, more resilient, and more caring.

Still others are tapping into wells of strength in their models to sustain their learners during this time of school disruption. For example, at Map Academy, disruption of education is not seen as a problem to be overcome. Rather, it has been one of the defining features of the school’s model since it opened in September of 2018. Map Academy, a charter public high school in Plymouth, MA, serves students for whom traditional school has not worked, including youth who have dropped out or are at risk of leaving school without a diploma. In the eyes of Map Academy’s founders, the traditional school system failed these students. For that reason, the school was intentionally designed to epitomize disruption—to dismantle a model that did not work for their learners in order to reimagine one that would.

In this edition of Friday Focus: Practitioner’s Guide to Next Gen Learning, Map Academy’s co-directors and co-founders Rachel Babcock and Josh Charpentier describe some of the fundamental differences between Map Academy and more traditional high schools, including:

- Why a school like Map Academy was needed

- How the model supports previously marginalized learners to be successful

- How “designing for the margins” prepared the school to meet challenges associated with the COVID-19 pandemic

How Map Academy Started…with a Map

Before founding Map Academy, both Josh and Rachel served as leaders of the Alternative High School Program at Plymouth Public Schools. Working in those roles, they saw the shortcomings of both the traditional model and the available alternatives, many of which were focused exclusively on credit recovery.

As Josh describes, “We were putting Band-Aids on what needed surgery. We spent so much time and energy getting students to graduate that we lost sight of life after high school. We didn’t ask, ‘Are they ready for June 8—the day after graduation?’”

“The kids were not getting a high-quality high school experience,” Rachel adds. “Credit recovery was about checking the boxes that students had been there, not what they learned and did. Their options were bleak.”

Map Academy was born from Josh and Rachel’s desire to provide students in their community with a new option, a true alternative to high school or credit recovery programs. The “Map” in the name, they explain, is not an acronym. It reflects the school’s personalized approach, and it invites all learners to “find your way here,” to graduation and success in life beyond that milestone.

The name also refers to an actual paper map of Plymouth, now on display in the school’s lobby. Josh and Rachel used the map as a visual whenever they spoke to community stakeholders about the learners who were not being served by the current system. Using 2016 data, Map Academy’s future founders placed colored dots on the map—over 390 in all—to represent students who had recently dropped out of high school, were enrolled in alternative programs, or were middle schoolers at high risk of dropping out of high school as indicated by Massachusetts’ Early Warning Indicator System data.

“These dots are not just stickers. They are real kids and families,” Josh explains. “We brought this map every place we went and gave the presentation to everyone who would listen,” he recalls. “We realized that if we created our own school, we could serve the kids who needed us most. Rachel and I did not set out to open a charter, but to solve the problem of so many kids dropping out.”

Engaging the Disengaged

Flexibility has been our greatest strength. To serve learners who have disengaged—those at the margin of the margin—we unscripted a lot of the high school stuff that was seen as unchangeable. That has allowed us to ideate, find opportunities, and develop a lab school mentality.

— Rachel Babcock

Broadly speaking, key features of the Map Academy program may sound familiar to educators who embrace next gen learning: competency-based progression, flexible pathways, career development, and a focus on building a supportive culture. Yet, as Josh points out, their school actively recruited learners “who had not been well-served by schools and who did not have a lot of trust. We had to repair the harm done by a system that had failed them.”

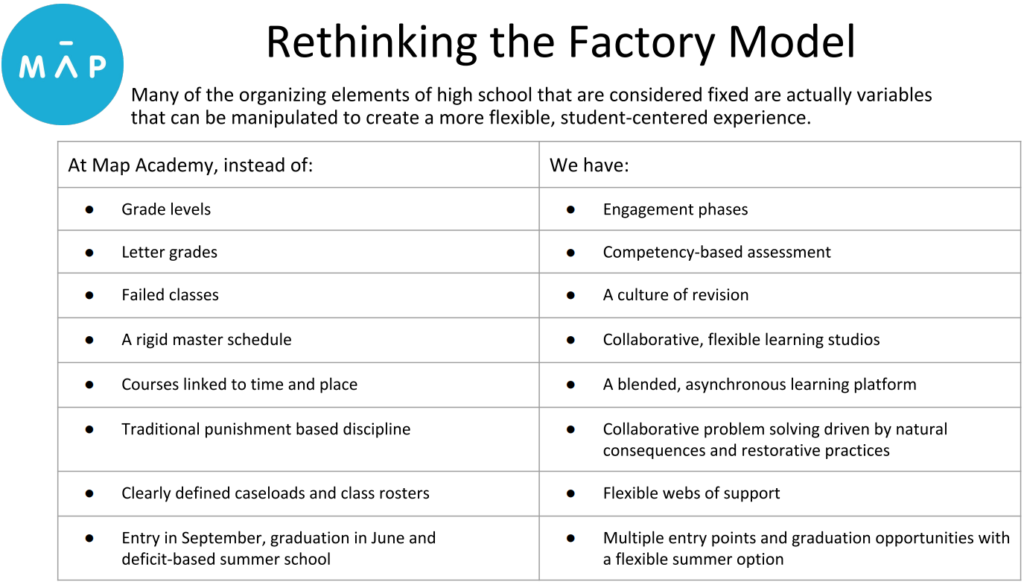

Key differences between traditional high school programs and the Map Academy model

For Map’s founders, “doing high school differently” was more than a slogan about being innovative. It was, as Rachel puts it, a commitment made to “youth who had been traumatized by school,” a promise that Map Academy would provide a genuinely alternative pathway to graduation and future success.

Rather than replicating or making incremental changes to traditional models, Map Academy was predicated on a complete overhaul of high school as students had experienced it in the past. Traditional practices like letter grades and grade levels, master schedules, the classroom as the sole locus of learning, the September-to-June school year, and even the notion of a “class roster” were all eliminated.

Instead, every aspect of a Map Academy learner’s experience is personalized and flexible. Students can access the blended learning platform at school, from home, or any other location. They achieve and demonstrate mastery of the competencies along their individualized pathway in their own time and at their own pace. At every step, they are provided with wraparound support, not just from a specific teacher or case manager, but via a web of nurturing adults, both inside and outside of the school community.

Not surprisingly, finding mentor models for the new school was a challenge for Josh and Rachel. Seeking guidance and inspiration, Map’s founders conducted research into various programs over the course of 2016-2017, their planning year. With grant funding, primarily from the Barr Foundation, they visited alternative schools across the country. Rachel recalls that, although they saw quite a few great models, it was very rare to find alternative programs that were specifically designed to meet the needs of the students she and Josh intended to serve, learners who had entirely disengaged from the educational system.

Map’s founders did adopt some practices from schools they visited, such as the student progress tracker Bronx Arena High School in New York uses in their competency-based model. However, as Rachel describes, the greatest value of these visits arose from the educators they met and the mindsets the school leaders modeled. “The places that felt the closest to what we were trying to do were those with lots of tolerance for uncertainty,” she explains. “Those were the stories that resonated, so even though we did not find a school exactly like what we had in mind, we saw the flexibility and made that part of every step in our school design process.”

The result, according to Josh and Rachel, was a student-centered model designed around each individual student. “There are certain things we know students need,” Rachel notes, “but it’s not a formula. We ask, ‘What does this student need?’ We take very seriously the autonomy we have to do the opposite of just checking boxes.”

Challenges and Assets in a Difficult Time

We set out to create a really supportive culture and community, and we nailed it. But this is a population who has been failed by school for over a decade; they don’t come in and trust us automatically. It’s been hard enough to get students to accept our support when we see them every day. Doing everything remotely now has been extremely challenging.

— Josh Charpentier

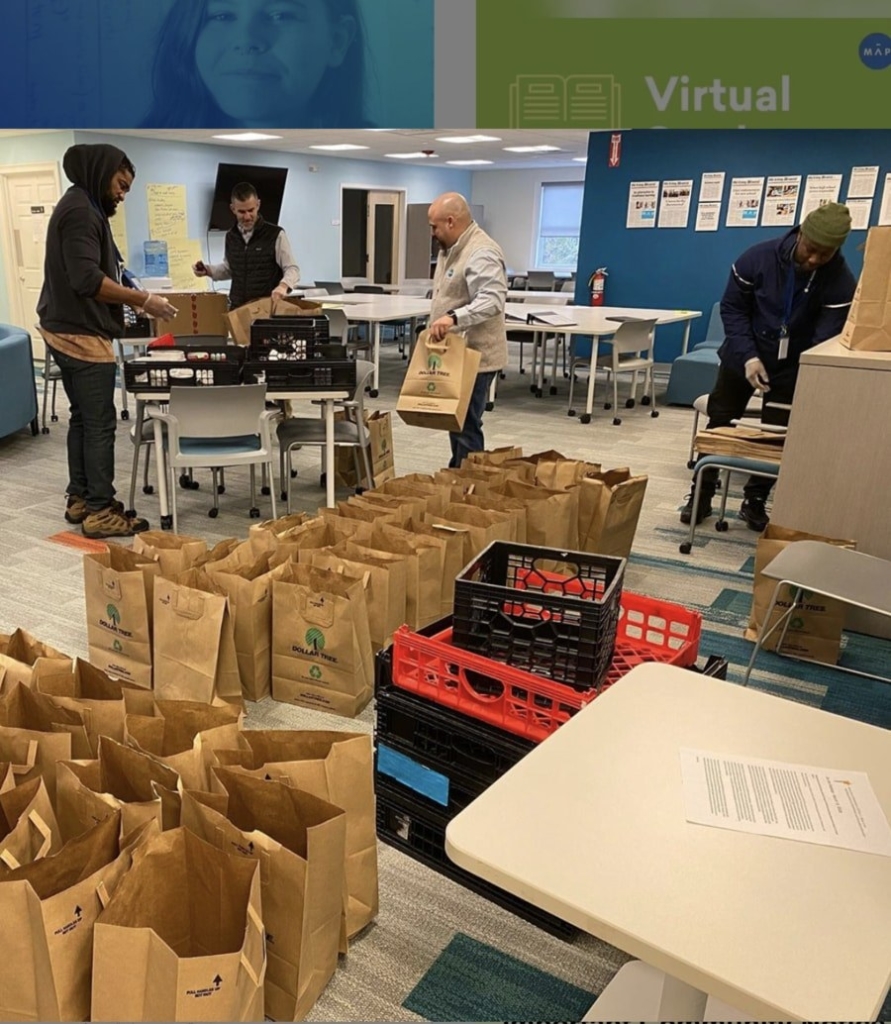

During the pandemic, Map Academy delivers food and supplies to 50 families a day and also uses those visits as support touch points. (Courtesy of Map Academy)

Like the vast majority of schools in the U.S. and internationally, Map Academy closed the school building in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Both Josh and Rachel acknowledge that providing learners with wraparound support—one of Map Academy’s key design elements—has been difficult to translate to a remote learning context.

In response to the school closure, the school has made daily deliveries of food, household needs, work materials, and tech items, instituted Zoom and FaceTime student check-ins, and created a virtual student center. Teachers at Map Academy have also worked full-time throughout the health crisis. As Josh explains, “We are communicating to our staff that our kids need us to be there for them.”

According to Rachel, the school also hosts virtual community meetings, “to put ritual back into the day for students. We find ways to add back in some of the community we’ve lost, but we’re still working at that. In spite of how flexible we are, our students and families will be the most impacted,” she explains. “We cannot replicate the level of support, which is so intertwined with the academics. That has been very hard.”

Alongside such challenges, however, Josh and Rachel also identify strengths of their model that contributed to a nimble and resilient response to the pandemic. One of these, Rachel points out, is the use of anytime, anywhere learning. “Our students have life experience and strengths but also responsibilities. That’s why we had to adopt an asynchronous and flexible platform. Four months ago, people did not get what I meant by asynchronous,” she recalls. “I could almost see their effort to recall their Latin roots. All of a sudden it is the buzzword of the century. There’s a sense of it being temporary due to the virus, but this is an opportunity for us all to see that this is how learning could be.”

“Another good thing with our model is that it’s competency-based and self-paced,” Rachel adds. “Some students are saying, ‘I can’t learn like this,’ but as things stabilize, they can pick up where they left off. They have slowed down, but they are not left behind. They know the ship has not sailed away without them.”

Similarly, the competency-based approach is not hampered by grade levels and the traditional school calendar. According to Rachel, it means that learners “don’t have to worry about promotion. There may be a gap, a significant loss of time, but it isn’t exacerbated by some line in September.”

Learners are not left behind, she explains, but they are not artificially moved ahead, either. “They actually have to do the work and meet the requirements. There is no such thing as fake progress here, none of the well-meaning ‘pushing along with a D-minus’ that students may have experienced in the past. They actually have to do the work and they know it.” In spite of the enormous challenges, Rachel reports that the number of students who’ve made progress and earned credit during the closure has been a pleasant surprise.

As for Map Academy’s future, the leaders are looking closely at their responses to the school closure to determine which ones were, as Rachel puts it, “crisis changes” and which ones might lead to a new normal. “We want to leverage our strengths but not be complacent. We don’t have to reimagine everything, but that being said, we have a unique opportunity to make changes.”

“Rachel and I are using the pandemic to find silver linings that will help us iterate on our model,” Josh explains. “We are taking a pause to make us a better school when we open in the fall.”

Resources

- For an introduction to Map Academy and what its model set out to accomplish, check out this brief video, Our Story.

- This Students at the Center Presentation provides more detail about Map Academy’s key design elements, including phases of engagement, webs of support, and trauma-informed strategies.

- For the next month, Education Disruption, the Map Academy podcast series, is spotlighting the experiences of this year’s graduates. Listen each week to the stories of six members of Map Academy’s graduating class of 2020.

- In the blog post “Schools as Communities of Care,” Jeff Heyck-Williams, director of curriculum and instruction at Two Rivers Public Charter School in Washington, D.C., explores how schools that operate as communities of care develop a sense of safety, a sense of belonging, a sense of joy, and a sense of hope in all of their students—even in the wake of a pandemic.

- NGLC’s School Closures: Practitioner Resources for Teaching & Learning hub now features a new strand to support schools and districts as they plan to safely and equitably reopen schools. We invite you to use and/or contribute resources to this ongoing crowd-sourced document.